The Miller–Urey experiment, conducted in 1952 by chemists Stanley Miller and Harold Urey, is one of the most iconic scientific studies in the field of abiogenesis — the study of how life might have originated from non-living matter. Designed to simulate the conditions of early Earth, this groundbreaking experiment demonstrated that simple organic molecules, including amino acids, could form spontaneously when exposed to energy sources such as lightning. Although modern research has refined and expanded our understanding of Earth’s early atmosphere, the Miller–Urey experiment remains a landmark demonstration that the building blocks of life can emerge through natural chemical processes. Its findings continue to inspire research in chemistry, planetary science, and the search for life beyond Earth.

The experiment captured the imagination of scientists worldwide because it provided the first laboratory evidence supporting the theory of chemical evolution — the idea that life originated through gradual increases in molecular complexity. Even seventy years later, the Miller–Urey experiment remains foundational to our understanding of prebiotic chemistry.

How the Experiment Worked

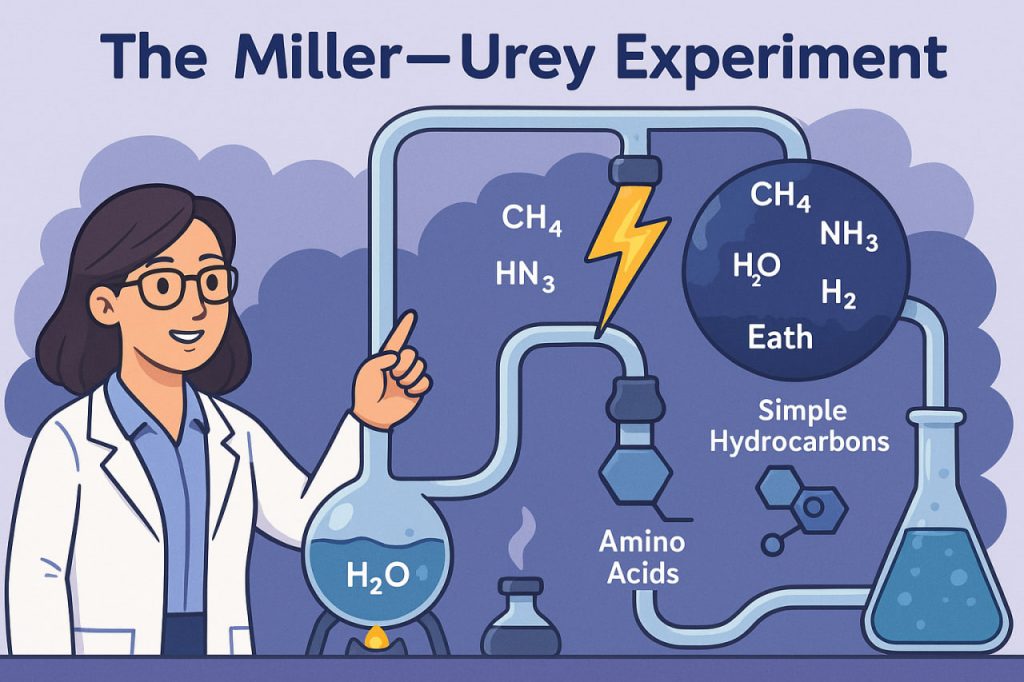

Stanley Miller designed a closed glass apparatus that mimicked what was then believed to be Earth’s early atmosphere. The system contained:

- methane (CH₄)

- ammonia (NH₃)

- hydrogen (H₂)

- water vapor (H₂O)

These gases circulated through the apparatus while sparks — representing lightning — supplied energy to trigger chemical reactions. Water was heated to simulate ocean evaporation, and the vapor interacted with the gases in the “atmosphere” chamber. According to origin-of-life researcher Dr. Naomi Wexler:

“The brilliance of the Miller–Urey experiment lies in its simplicity —

it showed that nature itself can build the chemistry needed for life.”

After several days, the liquid in the system became rich in organic compounds.

What the Scientists Discovered

When Miller analyzed the results, he found that the experiment had produced:

- amino acids — the building blocks of proteins

- simple hydrocarbons

- organic acids

- other prebiotic molecules

In total, more than 20 different amino acids were eventually identified in Miller’s preserved samples. This discovery provided strong evidence that early Earth could have supported the chemical steps leading toward life.

Modern Reinterpretations

Although scientists now believe Earth’s early atmosphere was likely less reducing than Miller assumed, later versions of the experiment — using more realistic gas compositions — have still produced organic molecules. Additional energy sources such as ultraviolet light, volcanic activity, and hydrothermal vents also support the possibility that prebiotic chemistry could occur in multiple environments.

Further research on Miller’s archived samples, analyzed decades later with modern instruments, revealed even more complex organic molecules than first realized. This confirms that the chemistry of early Earth was likely diverse and highly productive.

Why the Experiment Matters Today

The Miller–Urey experiment continues to influence several scientific fields:

- Origins of Life Research — inspires modern studies on RNA, lipids, and early metabolic pathways.

- Astrobiology — helps scientists evaluate whether planets like Mars or Titan could support prebiotic chemistry.

- Planetary Science — guides models of atmospheric evolution and early planetary environments.

- Synthetic Biology — informs attempts to recreate life-like chemical systems in the laboratory.

Its historical importance lies not in proving exactly how life formed, but in showing that natural processes can create biological building blocks without any biological machinery.

Limitations and Criticisms

Despite its success, the experiment has limitations:

- Early Earth’s true atmosphere was likely less reducing.

- Amino acids alone do not constitute life.

- Additional steps — polymerization, membranes, genetic molecules — require further explanation.

Modern theories now incorporate hydrothermal vents, clay surfaces, lipid assemblies, and RNA-based systems to extend the story beyond Miller’s results.

Interesting Facts

- Miller carried out the experiment at age 23, under Urey’s supervision.

- Decades later, preserved samples revealed many more amino acids than initially known.

- Similar experiments using volcanic gases produce even richer organic chemistry.

- Some scientists believe lightning storms on early Earth occurred ten times more frequently than today.

- Miller joked that if life ever formed in his flask, he would be “very surprised — but very proud.”

Glossary

- Abiogenesis — the study of how life arose from non-living matter.

- Reducing Atmosphere — an atmosphere rich in hydrogen that promotes the formation of organic molecules.

- Amino Acids — fundamental building blocks of proteins.

- Prebiotic Chemistry — chemical reactions that occur before the existence of life.

- Chemical Evolution — gradual increase in molecular complexity leading toward biological systems.